In 1950, the U.S. Navy conducted a covert experiment to test the efficacy of a biological weapon

against a major North-American city. Dubbed "Operation Sea-Spray", the experiment saw bacteria

sprayed over the San Francisco Bay Area, affecting the air and water supply of the city.

The operation exposed approximately 800,000 Californian citizens to serratia marcescens and

bacillus globigii, bacteria that could cause illness in humans but were considered

somewhat benign.

Following the exposure, the city saw a spike in urinary-tract infections and pneumonia. The U.S.

Army went on to acknowledge the cases of pneumonia at a later hearing, but concluded that it was

purely coincidental, and that the urinary-tract infections were the fault of a hospital.

In August, 1949, The U.S. Army Chemical Corps sends special operatives from Fort Detrick to

infiltrate and spray bacteria into the Pentagon's air handling system to prove that the U.S. was

particularly vulnerable to bioweapon attacks.

On September 20, 1950, a U.S. Navy minesweeper sprayed serratia marcescens and bacillus globigii

into the San Francisco Bay Area from two miles offshore, using the region's fog as a carrier.

On September 22, spraying of the bacteria continued with it spreading 30-mile inland due to San

Francisco's fog aiding dispersal.

By September 23, samples indicated that widespread contamination was successful, with bacteria

detected in hospitals and public areas.

On September 25, it had been noted that the bacteria had spread 50-miles inland and had penetrated

indoor environments.

September 26 saw the minesweeper ceasing the spraying of bacteria as the active phase of the

experiment came to an end.

September 27 marked the final day of the experiment, with analyses revealing a coverage of 117-mile

radius with nearly all residents infected. The public are not alerted to the outbreak.

On October 11, Eleven patients were admitted to Stanford University Hospital with urinary-tract

infections caused by serratia marcescens. Three weeks later, a patient, Edward J. Nevin died from a

heart valve infection, purportedly linked to the bacteria. Doctors noted the rarity of such an

outbreak and published their findings.

The success of the experiment saw further interest in biowarfare testing, with the U.S. Air Force

requesting the U.S. Army Chemical Corps conduct further experimentation, leading to the 1953 "St.

Jo Program", which saw mock anthrax attacks on Winnipeg, Minneapolis, and St.Louis.

In 1977, senate hearings conducted by the Subcommittee on Health and Scientific Research of the

Committee on Human Resources saw the declassification of Operation Sea-Spray.

In 1981, the family of Edward J. Nevin sued the U.S. government for wrongful death,

alleging Sea-Spray caused his infection, but was dismissed due to insufficient

evidence.

In 2001, a San Francisco hospital saw an outbreak of meningitis caused by serratia marcescens,

renewing discussions of the long-term affects of Sea-Spray on the region.

With the immense success of Operation Sea-Spray, further tests were conducted into the late 60s.

From 1951 to 1952, the Dew trials were conducted to test the behavious of aerosol-based biological

agents by releasing around 250 lbs of fluorescent particles off the coast of Georgia

and South Carolina.

The Dew I trial began on March 26, 1952, when a Navy minesweeper released an aerosol cloud of zinc

cadmium sulfide offshore, which subsequently drifted over large areas of Georgia, North Carolina,

and South Carolina.

The Dew II trial saw the release of zinc cadmium sulfide and the plant spore, lycopodium, from an

aircraft.

1953 saw the initiation of the St. Jo Program, when the U.S. Air Force requested that the U.S. Army

Chemical Corp continue their experimentation.

The program saw biological simulants, such as anthrax, dispersed over St. Louis, Winnipeg and

Minneapolis from aerosol generators placed on top of cars. Local governments were informed that the

experiments were "invisible smokescreens" deployed to mask the city from enemy radar.

The conclusion of the program showed that large-scale deployment of bioweapons from land was

feasible.

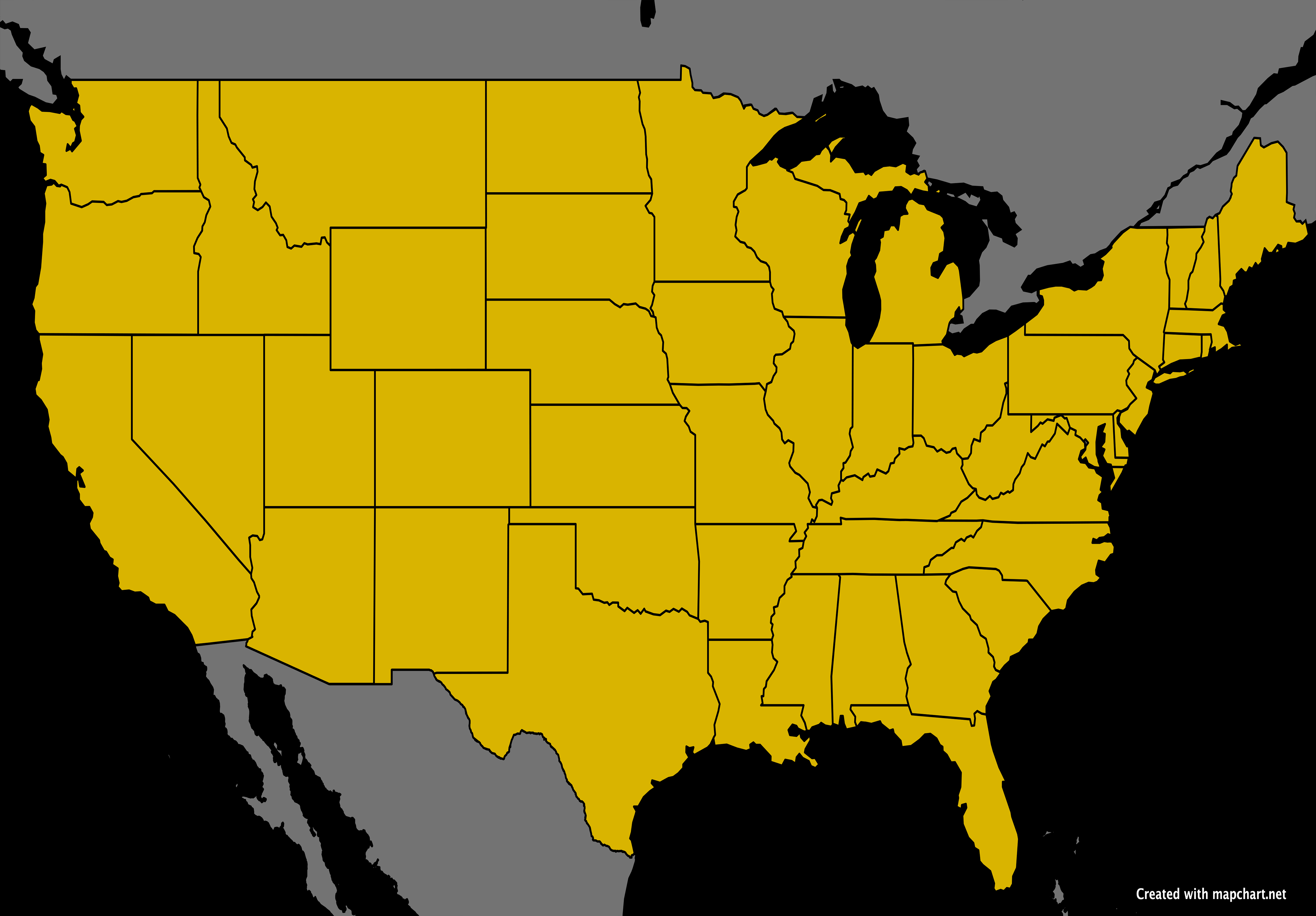

As a continuation of their findings, the U.S. Army Chemical Corp began Operation Large Area

Coverage in 1957, which saw the dispersal of fluorescent zinc cadmium sulfide from airplanes.

The operation saw several tests in which aerosols dispersed microscopic materials from South

Dakota to Minnessota, from Ohio to Texas, and from Michigan to Kansas.

The operation concluded that large-scale deployment of bioweapons from the air was not only

feasible, it was highly effective, with test particles spreading up to 1,200 miles from their

origin.

Part of the larger Dorset Biological Warfare Experiments that took place between 1953 and 1957

which aimed to determine the feasability of biological warfare against the United Kingdom from a

single ship or aircraft.

After intial test took place using zinc cadmium sulfide as a simulated agent, the experiments were

taken to the next level by using bacillus globigii on the town of South Dorset using the same test

method as Large Area Coverage.

The DICE trials, which took place between 1971 and 1975, saw the dispersal of serratia marcescens,

along with an anthrax simulant and phenol, across the same region.