Between 1920 to 1933, the United States underwent what has come to be known as the Prohibition Era:

a statewide crackdown on the production and distribution of alcoholic beverages. The Prohibition

was brought on by a combination of progressive reform, moral and religious beliefs, economic and

health advocation, and political pressure.

Many who opposed the new legislature would continue to drink, produce and sell alchohol illegally

and in secret, with criminals repurposing stolen industrial alcohol as one of their main methods of

redistribution.

As a response, the government demanded that increased numbers of toxins be used in industrial

alcohol, knowingly causing widespread sickness and death, and considering it largely collateral

damage and a means to an end.

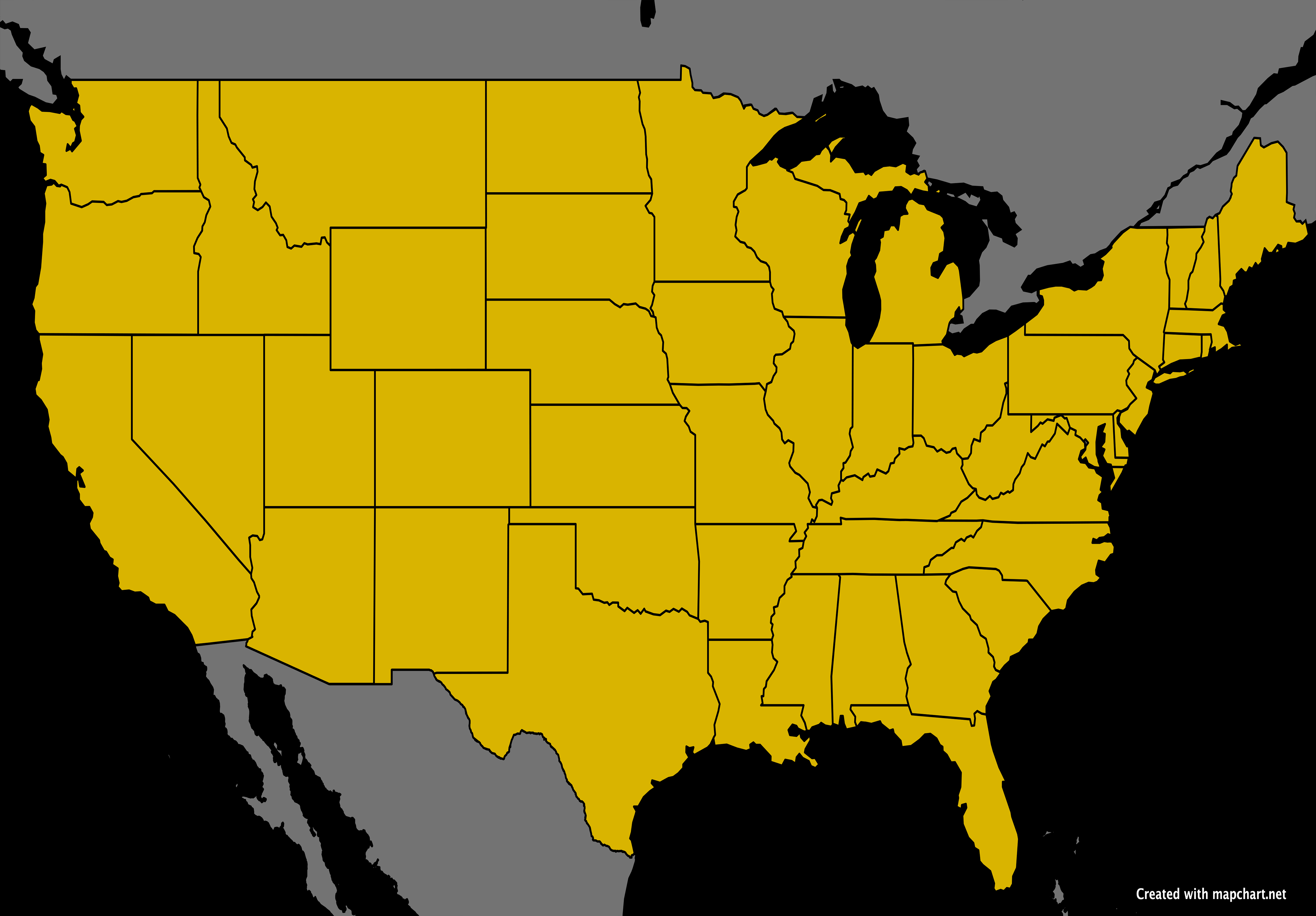

On January 16, 1919, Prohibition was introduced nationwide under the 18th Amendment to the

United States Constitution. The amendment outlined the legal framework for Prohibition that the

entire country would have to abide by.

[1]

On October 28, 1920, the Volstead Act was passed by Congress, which allowed the U.S. Government to

enforce the 18th Amendment. The Volstead Act would define what constituted as an "intoxicating

liquor" and established penalties for its usage and distribution.

In late 1926, new mandates saw companies adding additional, or increased levels of toxins to

their denatured alcohol.

On December 24, New York City's Bellevue Hospital admitted 60 patients, leading to 8 deaths.

On January 1, 1927, the death toll rose to 41 in Bellevue Hospital alone.

That year, Philadelphia reported 307 deaths, Chicago reported 163 deaths, and a Kansas county

reported around 15,000 poisonings. Cities reported large influxes of patients suffering from

gastrointestinal distress and chronic kidney damage, while hospitals recorded numerous cases of

heart palpitations and respiratory distress linked to tainted alcohol. New York City seized

480,000 gallons of liquor, with 98% containing toxic additives.

Despite the mounting casualties, the government were undeterred and continued to poison the

alcohol supplies. Seymour Lowman, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, who was in charge of

enforcing Prohibition laws commented:

The great mass of Americans do not drink liquor. There are two fringes of society who are hunting for "booze." They are the so-called upper crust and the down-and-out in the slums. They are dying off fast from poison "hooch." If America can be made sober and temperate in 50 years a good job will have been done.

- Seymour Lowman

"PROHIBITION: New Sponge",

1927

The person who drinks this industrial alcohol is a deliberate suicide…

To root out a bad habit costs many lives and long years of effort…

- Wayne B. Wheeler

"GOVERNMENT TO DOUBLE ALCOHOL POISON CONTENT AND ALSO ADD BENZINE; SMELL WARNS DRINKERS",

1926

In 1928, enforcement of Prohibition intensified, with around 75,000 arrests made. This, however, did not deter non-compliance, as the popularity of speakeasies flourished. New York Chief Medical Examiner Charles Norris, estimated that nearly all the liquor in New York City was toxic. He went on to speak out against the deliberate poisoning of citizens, and put the responsibility directly onto the government: [2]

The government knows it is not stopping drinking by putting poison in alcohol... Yet it continues its poisoning processes, heedless of the fact that people determined to drink are daily absorbing that poison. Knowing this to be true, the United States government must be charged with the moral responsibility for the deaths that poisoned liquor causes, although it cannot be held legally responsible.

- Charles Norris

1926

On February 14, 1929, the St. Valentine's Day Massacre took place, which saw the execution of

seven men who were associated with Chicago's North Side Gang. The incident was linked to Al

Capone's bootlegging industry, and highlighted the Prohibition's impact on escalating crime.

[2]

1930 saw an epidemic of leg paralysis, known as "Jake Leg", in those that drank Jamaica Ginger,

due to tri-ortho-cresyl phosphate contamination. It was estimated that around 35,000 to 100,000

people were afected due to the neurotoxin poisoning.

[2]

In 1931, public opinion on Prohibition started to rapidly plummet. The ongoing Great Depression

fueled arguments about the impact of Prohibition on the economy as anti-Prohibition groups

intensified

their lobbying.

[2]

On June 6, 1932, John D. Rockefeller Jr. denounced the Prohibition policies via a letter addressed

to the president of Columbia University, Nicholas Murray Butler, citing his disillusionment

caused by the failures of Prohibition.

[2]

At the Democratic National Convention that took place from June 27 to July 2, presidential runner,

Franklin D. Roosevelt promised a repeal of the 18th Amendment as part of his campaign. In his

speech, he highlighted the increase in organised crime, economic downturn, and the public health

crisis caused by poisoned alcohol.

[2]

On March 4, 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt was sworn into office.

[2]

On March 21, the Cullen-Harrison Act came into effect after being passed by congress. The act

supplanted the Volstead Act, allowing the manufacturing and distribution of beer and wine with an

alcohol weight of 3.2%.

[2]

On December 5, the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment, ending Prohibition across the

country, though some states continued its usage.

[2]

The controversial legislature saw a divide among the population, with those in favour of Prohibition being referred to as the "dry" movement, and those who opposed it as the "wet" movement.

One of the more effective political proponents of Prohibition, the ASL was led by Wayne B. Wheeler, who focused the group to ban alcohol. Their influence in politics allowed them to endorse anti-alcohol candidates and focus on aggressive tactics to create legislative change, helping usher in the 18th Amendment.

An influential temperance group that highlighted to women across the nation the role that alcohol consumption played in domestic violence and moral decay. The union would often hold rallies and distribute anti-alcohol literature to the masses.

Many Protestant communities, particularly those in rural or conservative regions, were in support of Prohibition due to their belief that alcohol consumption was sinful. Protestant clergy would preach of the importance of abstinence during sermons, and would partner with groups like the ASL.

Progressive activists saw Prohibition as a method of improving overall social reform. Progressive figures would bring attention to scientific studies to bring awareness to the dangers of drinking.

Industry heavies such as John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Henry Ford gave their initial support to Prohibition by providing financial backing to anti-alcohol groups. Rockefeller would go on to later oppose the movement for its failures.

The leading anti-Prohibition group, the AAPA consisted of business leaders and industrialists who collectively saw Prohibition as unadulterated government overreach. The organisation would shine a spotlight on the failures of Prohibition by reporting on the rise of bootlegging as well as the consequence of poisoning alcohol.

Brought together as a foil for the Women's Christian Temperance Union, the group consisted of mostly Republican socialites that argued Prohibition was a failed social experiment that saw an increase in crime.

Catholic communities opposed the ban, mostly due to the usage of wine in religious sacraments, viewing Prohibition as an attack on their religious practices.

Unions that represented workers, particularly those in the brewing and distilling trades, were staunch opponents of Prohibition due to the massive numbers of layoffs in alcohol-related industries. Unions were pivotal in organising protests and pointed out that legalising alcohol would create more jobs.

Urban areas that saw dense populations of Irish, Italian, Jewish and German communities argued that their cultural traditions were interwoven with alcohol. As such, these ethnic groups would undermine the law by protesting and fuelling the black market.

A major consequence of the Prohibition Era was the rise in the criminal element who took it upon

themselves to illegally produce, smuggle and sell their own alcoholic beverages. These people, or

"Bootleggers" as they were dubbed, would distill homebrews, such as beer, wine, bathtub gin and

moonshine, all while evading the law.

Al Capone, the criminal mob boss and co-founder of the Chicago Outfit, used Prohibition to help

build his criminal empire under the guise of providing a public service of supply and demand to

people on both sides of the divide:

When I sell liquor, it's called bootlegging; when my patrons serve it on Lake Shore Drive, it's called hospitality.

- Al Capone

One of the more effective crimes that became a staple of bootleggers, was stealing and repurposing industrial alcohol, which was often used for paints and solvents. In a bid to deter bootleggers from utilising industrial alcohol, the U.S. government responded by further poisoning it through a process referred to as "denaturing".

The denaturing process, which began much earlier than the Prohibition Era, saw toxic substances

being added to industrial alcohol in order to make it undrinkable. Bootleggers would hire chemists

to distill the chemicals out of industrial alcohol, thereby making it safe for consumption.

When the Volstead Act outlined the methods in which the government could enforce Prohibition, the

Treasury Department ordered manufacturers to increase the amount of toxic substances to their

product, or add new ones, to the point that bootleggers could no longer distill the alcohol to safe

levels. These substances included the following:

The fallout of intensifying the denaturing process was devastating. The increase in methanol saw between 50,000 to 100,000 US citizens become paralysed or blind, New York City alone reported over 1,200 cases of sickness, paralysis and blindness, with estimates of around 750 total deaths. Though total numbers are only estimated, it is believed that around 10,000 deaths were caused due to Prohibition poisoning.

The long-term effects of the Prohibition would see an erosion of public trust in officials and

highlighted the dangers of government overreach.

In a September 1991 issue of Milibank Quarterly, Harry G. Levine and Craig Reinarman claimed

that the U.S. government used Prohibition as a framework for the 1971 War on Drugs, utilising its

tactics, moral grandstanding and enforcement procedures:

The American temperance movement and Prohibition provided the major historical model for drug prohibition. The anti-alcohol crusade developed a single-minded focus on passing laws to outlaw the manufacture and sale of alcohol, a strategy repeated in the war on drugs. Both prohibition movements have used law enforcement to try to suppress supply and demand, both have increased the price and potency of the prohibited substances, and both have fostered organized crime and black markets.

- Harry G. Levine and Craig Reinarman

Milibank Quarterly,

1991

The 1920s saw a vast upsurge in federal power. And after 1933, that power did not diminish; it simply took on new directions. One of those directions was policing and surveillance. The prison industry vastly expanded, so many of the kinds of legacies that we live with were established during Prohibition.

- Lisa McGirr

2019